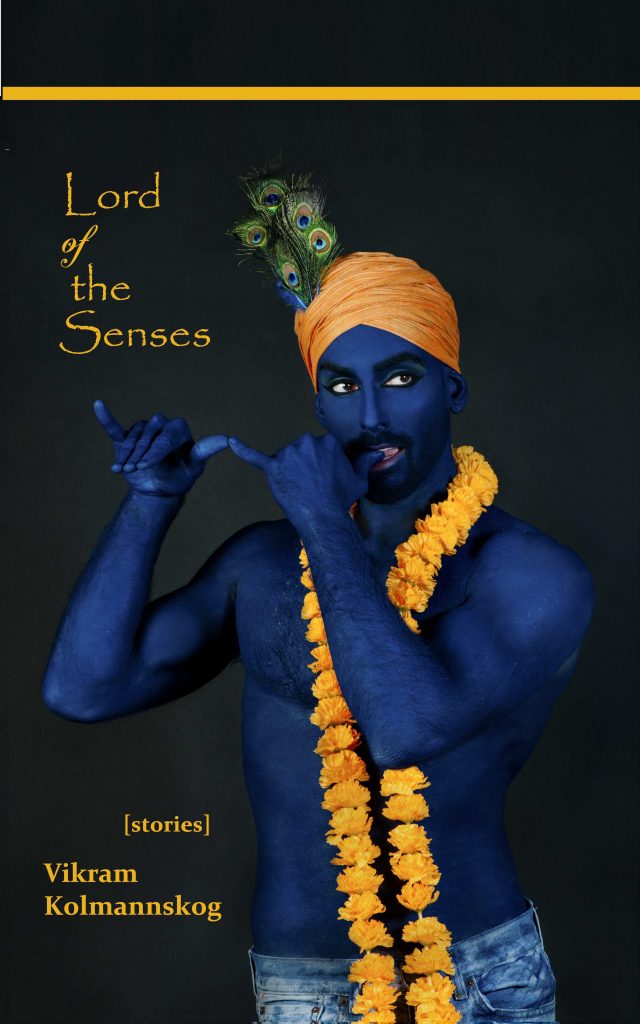

Vikram Kolmannskog is a gay, Indian-Norwegian writer, lawyer and psychotherapist. Lord of the Senses, a collection of stories, is his latest book. Vikram was interviewed for Gaylaxy magazine by John R. Gordon, his editor and publisher at Team Angelica, a queer-of-colour-centric press.

Who – or what – first inspired you to write? (prose fiction, that is.) Any childhood or school favourites, or books secretly discovered along the way?

For as long as I can remember, I have had a spiritual longing and loved stories. Whenever we visited my mother’s family in the UK – which we did quite regularly – I was fascinated by the Hinduism I saw there. I would constantly ask one of my aunts to explain things to me and she would tell me stories. Why does Ganesh have an elephant head? Krishna and Radha were lovers but not married? How can Ravan be the devotee of Shiva and at the same time a villain? Life in all its complexity is explored in the Hindu stories – as in other mythologies. One of the first things I wrote was a very short holy book. I wrote something about the importance of non-violence, being kind to all living beings; I don’t remember the rest.

Pappa also played an important role in introducing me to literature. Every night before bedtime at home in Norway, my little brother and I would sit in our pyjamas at the kitchen table, drink our milk and have a sandwich or something, and Pappa would read out loud to us. Mio, My Son by Astrid Lindgren is one of the books I remember. The important thing, more than the actual stories, what lingers, is Pappa taking the time to do this, and the sense of us sitting there together in the darkening evening.

How do you begin a story? What sort of inspiration makes you decide to set something down?

When I travel, I often get inspired; perhaps the movement, the change of scenery, does something with the mind and soul, introduces something or frees something. I wrote the first drafts of several of the stories in Lord of the Senses while staying in Bombay, a city I regularly return to.

I think it’s also about making myself available: When I go to Bombay, I often have few plans except to be with friends (and sometimes lovers), wander around and observe people and life, drink coffee, read and write. When I am aware of what is going on in me and around me, there is always something interesting happening.

Also, emotional life events, such as falling in love or heartbreak, often make me want to write; to somehow understand the process through creating a story, as well as turning it into more than my own personal pain or pleasure, a story that can be appreciated by more people, something particular and universal. For example, I wrote the first version of ‘A Safe Harbour’ soon after a very painful breakup.

Who would you say you are writing for, as your primary audience? I like that your work is not overly accommodating of non-Indian readers (while giving them enough contextualizing information to keep up.)

I guess the primary audience is people like me, LGBTQ folks with some link to India. I wrote several of the stories during (and as part of) the mobilisation for LGBTQ rights in India and many were published in Indian LGBTQ magazines such as Gaylaxy and Pink Pages. There has been a paucity of Indian LGBTQ literature. It is important to find some recognition in a story, I think, to have your identity and experience somehow validated. This has been important to me. Indian LGBTQ literature speaks to me in a very special way. And I wanted to contribute to this growing body of literature. We create a community, a sense of who we are and can be, through storytelling.

At the same time, I also hope that others who are not LGBTQ folks with a link to India will read and appreciate the stories. We all have the ability to empathise and expand ourselves through stories. And we are all human, after all; not that different, though the particularities of our longing, loving and heartbreak differ somewhat. I have read lots of books by white and/or straight people, with white and/or straight narrators and characters, and I have not found it difficult. All good literature deals with the complexity of life and can be enriching to everyone.

LGBTQ literature speaks to me in a very special way. And I wanted to contribute to this growing body of literature.

I don’t want to be overly accommodating of straight, white readers, though. Partly out of respect for the primary audience – LBGTQ folks with an Indian link, or more broadly queers of colour. White and/or straight people are often enough the focus in literature. It is also partly an aesthetic, stylistic consideration: When the narrator and protagonist in my story is Indian, it breaks with the whole illusion if common Indian words such as ‘Dalit’ and ‘Nanima’ are explained. I think there is enough information in all the stories for readers to understand everything without much knowledge of India, but it may take a tiny bit of patience and effort from straight, white people.

Much of your work feels autobiographical; do you see a division between writing that draws directly on your experience and writing that explores very different lives and settings, or are they very much part of the same creative act/process?

As soon as I recount or tell a story about an experience I have had, I am at a distance from the actual experience. Some things are included, some are not. What I remember and how I tell the story will depend on my current state of mind, the audience and overall setting. It is already a creative act, and fiction to some degree. In the stories that draw on my own actual life experiences, I also take the liberty to consciously change certain details and use my imagination.

However, I do feel there is a difference between writing that draws on my own experience and writing that explores a rather different kind of life. The latter requires more, or a different kind of, imagination and empathy, I guess. And I feel somewhat cautious when doing this, knowing that I cannot really and fully know how it is to be a Dalit or a woman, for example – or even someone who is born and bred in India, which I am not. Still, I do take a chance and write stories with such characters. Often I then seek feedback from someone who does identify with one of those groups. I think I can write about many things, but I do want to be aware of, and constantly explore, my own position and how it may influence my writing.

Many of the themes of this collection – modernity and tradition; the at times rather different values of Europe and India; the different outlooks of the generations on issues like caste, faith and sexuality – are usually shown in Indian and Diasporic literature as being inevitably in conflict with each other. Yet you tend to find an at times unexpected potential for co-existence between them. Was that something you set out to show – an optimistic, ideological vision, or is it one more simply rooted in your own life experience and observations?

I think it is both an ideological vision as well as something that is rooted in my own life experiences and observations. I believe there are various parallel traditions or tendencies within a culture and society. And this is not a linear development, always moving from oppression towards liberation, but rather tendencies that co-exist in the past and in the present.

In India there has been an oppressive tradition or tendency (‘conservative’ would not be precise), that is casteist and heterosexist. But there has also been a very inclusive and emancipatory one that has celebrated diversity and challenged oppressive practices such as casteism and heterosexism. The title story shows this clearly: The poet saint Meera, who lived 500 years ago, defied norms on sexuality and gender, leaving her husband, mixing with people belonging to different castes and religions and backgrounds, without shame. Today her songs about love are sung all over India. Another story, ‘Fucking Delhi’, shows that there has also been a very inclusive and loving tradition within Indian Islam – in parallel with a more oppressive one. This is the kind of tradition and tendency, inclusive and loving, that I want to contribute to.

In many of your tales there’s a harmony between the sensual/sexual and the spiritual that can be surprising to a Western reader used to Christian body-spirit duality/oppositionality. Given your predominantly Norwegian upbringing, was the harmony that you express – that your narrators literally embody – hard-won, even defiant; or was it more something that emerged naturally as you grew into yourself?

My spirituality permeates everything, including my sexuality and my writing. I grew up with a very inclusive Hinduism. Even in less inclusive versions, you would have to look long and hard to find anything in Hinduism that condemns homosexuality or queer lives more generally. In fact, there are stories that celebrate the diversity and fluidity of genders and sexuality. There are stories and traditions that celebrate the body and the sensual and include everything as holy. In one story, Vishnu turns himself into the female Mohini and arouses Shiva, they play sexually till they are satisfied, and then Mohini again becomes Vishnu and Shiva returns to his meditation. Awareness, compassion and playfulness are some of my guiding spiritual values. Cock, asshole and anal sex are – or can be – just as holy as everything else in this wonderful world and life.

I like to write about erotic encounters because it is a way to explore interesting psycho-social, existential and spiritual themes

Of course, I did have some shame around my sexuality while growing up – and still have – but this has more to do with growing up in a still largely heterosexist world. Furthermore, Norway used to be a Christian society, often quite puritanical. Even though it is now quite secular, shame does not disappear that easily. I think many people in Norway who identify as secular still struggle with shame related to their body and sexuality on some level.

Many of your stories are very sexually candid and unashamed in representing homosexual sex. You clearly enjoy writing sexually candid tales – one of the pieces in the collection was published in earlier version in the Erotic Review. Did you have to overcome a degree of self-consciousness to expose so fully your desiring – and acting – self?

I think ‘A Safe Harbour’, an early version of which was published by Erotic Review, was one of my first really sexually explicit stories. It has definitely been a process for me. I have had – and still have – some shame related to gay sex. Sex is after all a main reason why we were – and still are – considered sinful, criminal, sick or just dirty. Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, introduced by the Victorian-Christian British, criminalised ‘carnal intercourse against the order of nature’. This is a good reason to include gay sex in some detail in literature and elsewhere; let’s celebrate it, be excited by it!

More than it being a political-literary project, however, I like to write about erotic encounters because it is a way to explore interesting psycho-social, existential and spiritual themes: our desires, our prejudices, what we find attracting or repulsing, our insecurities, our sensitivity to rejection, our longing to be liked and loved, our longing to transcend our small selves and merge with someone or something else.

My mother and other family members have read some of the stories but not all, not the most sexually explicit ones, and I don’t really need them to do that. I don’t think I would want to read an erotic story that my mother wrote, if she ever did. Or maybe I would, actually. Anyway, the stories are out and everyone can read them if they want. I don’t want to be governed by a shame that is damaging to our liberation and growth.

Are there any in particular LGBTQ authors who inspired you?

I remember enjoying A Suitable Boy by my namesake Vikram Seth when I first read it. As a young teenager struggling with my outsider identity in Norway, I enjoyed being in the Indian universe of the book. At the time, I didn’t know that he was also queer – nor did I myself identify as queer. Perhaps there were also queer hints or subtle things in the book that resonated with that part of me. Stories really can help one feel at home in the world, I think, and that is quite something.

Another book that I read and appreciated early on in life is Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin. How amazing is that, a Black, queer man writing about same-sex love in 1956! And writing so well!

I should also mention Osman Diriye’s Fairytales For Lost Children here. I was so enthusiastic when I read these stories; well-written stories by a queer Somali, sometimes quite sexually explicit, stories from Somalia and Kenya and the UK! I had never read anything like that before. I had to look up the publisher. And that was the start of my relationship with Team Angelica, a team I am so much in love with now.

And, finally, there are the Indian LGBTQ writers: Raj Rao, Sandip Roy, Vasudhendra, Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, and Rahul Mehta.

What’s your favourite city to visit? To live in?

First is Bombay. Istanbul and New York are other cities that I like. I like cities by the sea. Despite being inland, I also like Berlin. They are all cities where there is much queerness, and a vegetarian can eat well.

Oslo is my favourite city to live in. It is just the right size and has a great location. I can walk or bike from my flat to most places I want to go to. After 30 minutes on bike, I am in the forest by the fjord and can bathe in salt sea water. After a 30 minutes’ tram ride I am up in the forested hills. Most importantly it feels like home, with the language and culture I grew up with. And, thankfully, it has become a very diverse city. I can love and hate Oslo and Oslo people in a very intimate way, like you can love and hate only family.

The Kindle version of Lord of the Senses is out on 23 August. The paperback is out on 6 September and can be pre-ordered on Amazon.in

- Film Kuch Sapney Apne Celebrates Diversity and Family Acceptance, and Stars Parents and LGBTQ+ Members in Cast - February 25, 2025

- Chennai Rainbow Film Festival 2025 Celebrates Diversity and Artistic Excellence - February 24, 2025

- #UNLABEL #BORN COLOURLESS: Absolut Mixers Calls for a World Without Labels - January 20, 2025