This week marks a full nine years since millions of adult Indians were unburdened of a pernicious law – Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code – which criminalizes consensual non-procreative sex between people (“Whoever voluntarily has carnal intercourse against the order of nature…”). On 2nd July 2009, in finding Section 377 unconstitutional, the Delhi High Court struck the law down as it applied to consensual adults, emphatically pointing out how it violated their fundamental rights – to life and liberty, to privacy and autonomy, to equality and expression. Howsoever much some may argue that the law does not specifically connote application to a particular group of people, the fact is that in its archaic and moralistic formulation and intent it was directed against homosexual behaviour (and until recent law reform also used in cases of child sexual abuse).

Alas, India should have been speaking of Section 377 in the past tense. But in its rejection of the Delhi High Court judgment, the Supreme Court in 2013 reinstated the law, through its shameful ruling in SK Koushal v Naz Foundation & Others.

To indulge for a moment, imagine an India where the shackles of Sec 377 have been broken once and for all. Millions of Indians would have been positioned to take a crucial and certain step in their emancipation. And, today they would have been almost a decade into that journey of hope; not re-oppressed by an atrocious law that allows the government to enter into private domains where it has no business to venture. Queer Indians would not have to continue to suffer the ignominy of ostracization by their families, blackmail from the public, violence by the police, scorn in media, or the constant fear of being tagged and threatened as criminals. Undoubtedly, none of these oppressions would have ceased because of the removal of Sec 377. But as certainly, two things would have happened – the ability to fight back and resist such tyranny and abuse, and the blossoming of self-worth and self-respect that comes with the court’s acknowledgment of queer people’s dignity. The diversity of human experience would have found a moment of celebration, instead of an occasion to subjugate difference. We could have been witnessing social and familial support, reduction in violence and adverse health outcomes such as HIV and mental health challenges, and greater discussion and understanding of varied sexualities.

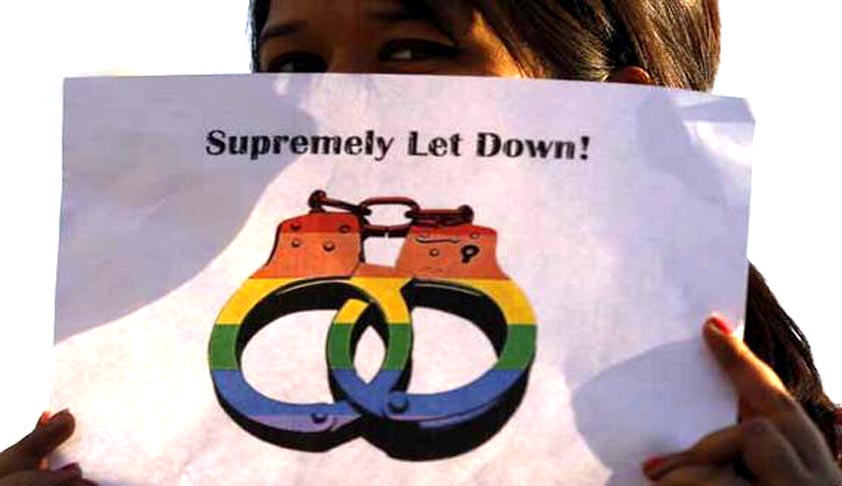

Supremely Let Down

Yet, we are not at that good place today. Instead, we find ourselves in a repressed re-criminalized situation. But there is hope, and it comes from a decision of the Supreme Court itself. In August 2017 the court emphatically upheld the fundamental right to privacy, and while doing so it evoked aspects of sexual orientation, which is at the heart of the claims to strike down S377. With great humility, the court recognized its own ruling in Koushal as “flawed” and,

“…misplaced because the invasion of a fundamental right is not rendered tolerable when a few, as opposed to a large number of persons, are subjected to hostile treatment. The reason why such acts of hostile discrimination are constitutionally impermissible is because of the chilling effect which they have on the exercise of the fundamental right in the first place… The chilling effect on the exercise of the right poses a grave danger to the unhindered fulfilment of one’s sexual orientation, as an element of privacy and dignity.”

Referring to Koushal’s egregious logic it said:

“That ‘a miniscule fraction of the country’s population constitutes [LGBT]…is not a sustainable basis to deny the right to privacy. The purpose of elevating certain rights to the stature of guaranteed fundamental rights is to insulate their exercise from the disdain of majorities… The guarantee of constitutional rights does not depend upon their exercise being favourably regarded by majoritarian opinion… Discrete and insular minorities face grave dangers of discrimination for the simple reason that their views, beliefs or way of life does not accord with the ‘mainstream’. Yet in a democratic Constitution founded on the rule of law, their rights are as sacred as those conferred on other[s]… Sexual orientation is an essential attribute of privacy. Discrimination against an individual on the basis of sexual orientation is deeply offensive to the dignity and self-worth of the individual.”

This decision was seen by many who have been contesting the validity of Sec 377 as an opportunity to return to the court and seek the striking down of Sec 377. Soon after the Koushal judgment in 2014, many who contested Sec 377 initially including Naz Foundation India and Voices Against 377 filed curative petitions seeking the setting aside of that judgment on the basis that it caused a gross miscarriage of justice. These curative petitions have been pending before the Supreme Court since then.

In mid-2016 two writ petitions were filed under Article 32 of the Constitution (which enshrines the fundamental right of individuals to seek redress for the violation of other fundamental rights before the Supreme Court), again challenging the validity of Sec 377. In Akkai Padmashali & others v Union of India, the petitioners bring to the fore the concerns of transgender people’s continued criminalization under Sec 377 despite and in contradiction of the court’s own judgment in NALSA v Union of India recognizing transgender people’s fundamental rights. The other petition by a group of “highly accomplished” gay people in Navtej Singh Johar & others v Union of India, argues that it raises issues on the constitutional validity of Sec 377, which have not been considered by the court in the Koushal case thereby justifying that it be heard.

On 8 January 2018 the Navtej case came up before the Supreme Court, much to the surprise of parties who had filed curative petitions. The court noted that the Koushal decision required “re-consideration”, and referred the Navtej petition to a larger 5-judge bench. Despite the ‘go-it-alone’ approach of those involved in the Navtej case, this outcome is positive: “reconsideration” means that the court is going to reopen the whole issue on the validity of Sec 377. In its order of 8 January the court also noted that curative petitions stood “on a different footing” and were pending hearing before a 5-judge bench. Presumably then, the Navtej petition is to be heard independently from the curative petitions. The 5-judge bench, which heard the Aadhaar validity case in early 2018 has listed the Navtej case after some other cases. Although it is unclear how long these other cases will take, their hearings are likely to begin shortly.

It would be fair to assume that the Supreme Court will hear on the validity of Sec 377 in August/ September 2018.

As the curative petitions were not listed before this 5-judge bench or any other bench, and in order to ensure that any decision of the court in the Navtej case is informed by the vast layers of nuance and arguments developed over the course of the hearings before the Delhi High Court and in the Koushal case, several of the parties who had curative petitions pending, have applied to intervene and be heard in the Navtej case. These parties include Naz India, Voices against 377, mental health professionals, and university teachers. All of these intervention applications will now be listed and taken up by the 5-judge bench when it hears the Navtej petition, although there is no certainty that the interventions will be allowed.

Keshavv SYru

In late April, hotelier Keshav Suri also filed a writ petition challenging the validity of Sec 377. In order to ensure that petitions which are far more representative of queer experiences with the law are heard by the court, and to demonstrate the real impact of criminalization and marginalization on queer lives the Humsafar Trust, and Arif Jafar, a queer activist who was arrested for abetting Sec 377 in Lucknow in 2001 also filed writ petitions. Most recently, a group of present and former IITians has filed a similar writ petition. Further petitions are also underway, which represent others who have been part of the struggle against this law over several years – to share their extensive experience on the impact of Sec 377, and to articulate the diversity of this experience from various socio-economic, sexuality, gender identity and geographical perspectives, dispelling any possible impression that the Sec 377 case is an elite concern, while also reaffirming the representative and participatory nature of this case.

These various petitions taken as a whole can only strengthen queer claims to the removal of Sec 377, which we will hopefully be able to speak of in the past tense sooner rather than later.