As a queer woman visiting Delhi, Sarah Holland Bacot has been told that Delhi Metro is concerned for women’s safety, but as she enters the terminal, it is unclear whom and what they are working to protect

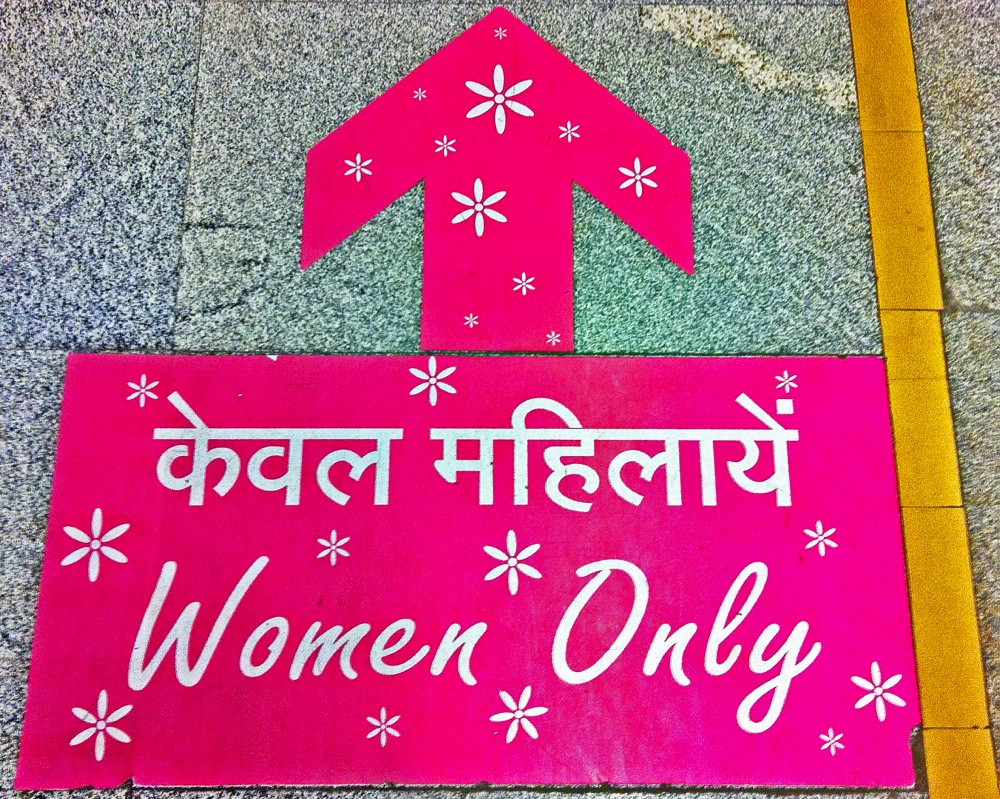

Delhi Metro is concerned about women’s safety. The signs plastered on the walls remind me of this.

As I approach the “For Ladies Only” sign on the women’s metal detector, I already feel the eyes on me. Three to one the woman responsible for waving the wand will ask me, “Are you a woman?” Sometimes it is a less threatening curiosity. When I answer, she will smile and say, “Oh, we were confused,” or nod politely. On other occasions the question comes with a meanness common to all schoolyard bullies who pick on the kids who are different. I know these guards because they wear not a smile but a sneer. The question comes loudly and with menace, “Are you a woman?” The women in line behind me titter or laugh outright and my face gets hot while she waves the wand and finds my curves. This is the evidence she couldn’t see well enough a moment before, the same evidence that keeps me from the men’s line where I would promptly be redirected, put through the process again.

When I make my way to the train, I have the mental debate. If I enter the mixed car when it is crowded, and someone realizes I am not a man, I will potentially be reminded by a leer or a stray hand why the women’s car exists in the first place. If it is not crowded, the stares last the entirety of the ride, possibly driven by curiosity, possibly by judgment. Maybe if I were not (made to be) so acutely aware of myself as an ambiguous creature, I could write this off as part of being a tourist with blonde hair, but it is too late for that.

Delhi Metro is concerned about women’s safety, so I wait near the women’s only car where I can feel safe.

A security guard catches my eye and looks me up and down. I straighten my back so that maybe she will notice slopes and softness, something just feminine enough. She walks to the left for another angle. I fail the test. She berates me and points to the mixed gender car, telling me to leave in front of the group of women who are waiting for the train. I have gone mute and my face burns and the tears threaten because this is humiliation and it is familiar. This is not happening once but once again and it has been a long day. Someone finally tells her, “No, she is a lady,” and the guard backs off, but she laughs as she does so because there is no need to apologize. The mistake is not hers; it is mine. She keeps staring, along with half of the other women waiting to board the train.

Delhi Metro is concerned about women’s safety, but sometimes I take an auto just to avoid the exhaustion of being safe.

Because I am just a passenger here in Delhi, I think of the permanent residents, the butch women, the trans women, the gender queers of the city. This kind of safety is not for them. This is the kind of safety that denies their existence. Will the Delhi Metro build a car for all of those who cannot (will not, do not want to) be defined?

That is the problem. The solution to issues of sexual harassment is not to stop those who harass but to separate those who are most often at risk, to make them aware of their place apart, to tell them where to be and when and how. The walls grow taller and any room for variance shrinks and shrinks because if the solution is to separate into boxes, then we must all fit.

As new women enter the car at each stop, the process repeats.

“This is the women’s only car.”

“I am a woman.”

“Oh.”

A woman who had lowered part of her hijab to use her cell phone catches my eye and immediately covers herself again.

I realize then: She is as uncomfortable with my presence as I am with her stares. Nobody is comfortable. We lock eyes and I am sure that neither one of us feels safe. We have both been told that this is a space for us,thespace for us, and as a result, the space has to meet all of our standards and expectations. This is an impossibility not recognized by those who made a box to protect women from everything outside rather than ridding the outside of all of those things that make us unsafe. There is no better way to maintain the status quo than to put the responsibility on the victim and not the offender. There is no better way to ensure that those who are vulnerable meet the expected standards, lest they be accused of bringing about their own assault, than to grant them protection through separation and a set of rules for their own good.

I am reminded by my friends to be home early, to take an auto instead of walking, to avoid walking alone if I can. These are my responsibilities. The Delhi Metro has done its job.

Finally we reach my stop. I am scared but not shocked when the white car pulls up and two men ask me where I am going as I wait for an auto outside the station at just past 10pm. The auto driver who slows for me is intoxicated but he is the only one who has stopped in the past five minutes. There is no one else outside the metro and the men are stalled at the corner, still watching me. This is what I get for having a social life that reaches past dinner time. I take the risk of the auto and their car follows us, pulls up next to us. They watch me and I reach for my cell phone, just in case, while my auto driver hiccups and tries to negotiate a higher price. They stay near us for a few minutes before peeling off and I am so relieved even as the hiccups continue.

I think of the woman and her veil, of the queens and queers who do not fit, of the laughter and shame that followed me home along with that white car.

I shouldn’t let it worry me. After all, Delhi Metro is concerned about women’s safety.

- Delhi Metro And Women’s Safety - February 10, 2014