On Thursday 6th September 2018, I woke up in a hotel room in Verona, Italy, in the city of Romeo and Juliet. The trip was a gift from my mother. There are many kinds of love, of course, romantic, motherly, friendly, social, political, divine.

Mamma was born in Kisumu, Kenya, in 1947, the same year as Independent India. She tells me that Bapuji, her father, always used to say that she came with liberation. Mamma’s family was part of the Indian diaspora in East Africa. As a teenager, she witnessed and celebrated the liberation of Kenya from the British. Later, studying in the UK, she participated in student demonstrations against racial discrimination and other forms of social injustice. After finishing her studies, she wanted to travel the world. First stop was Norway. It was meant to be only a short adventure, but then she met my father.

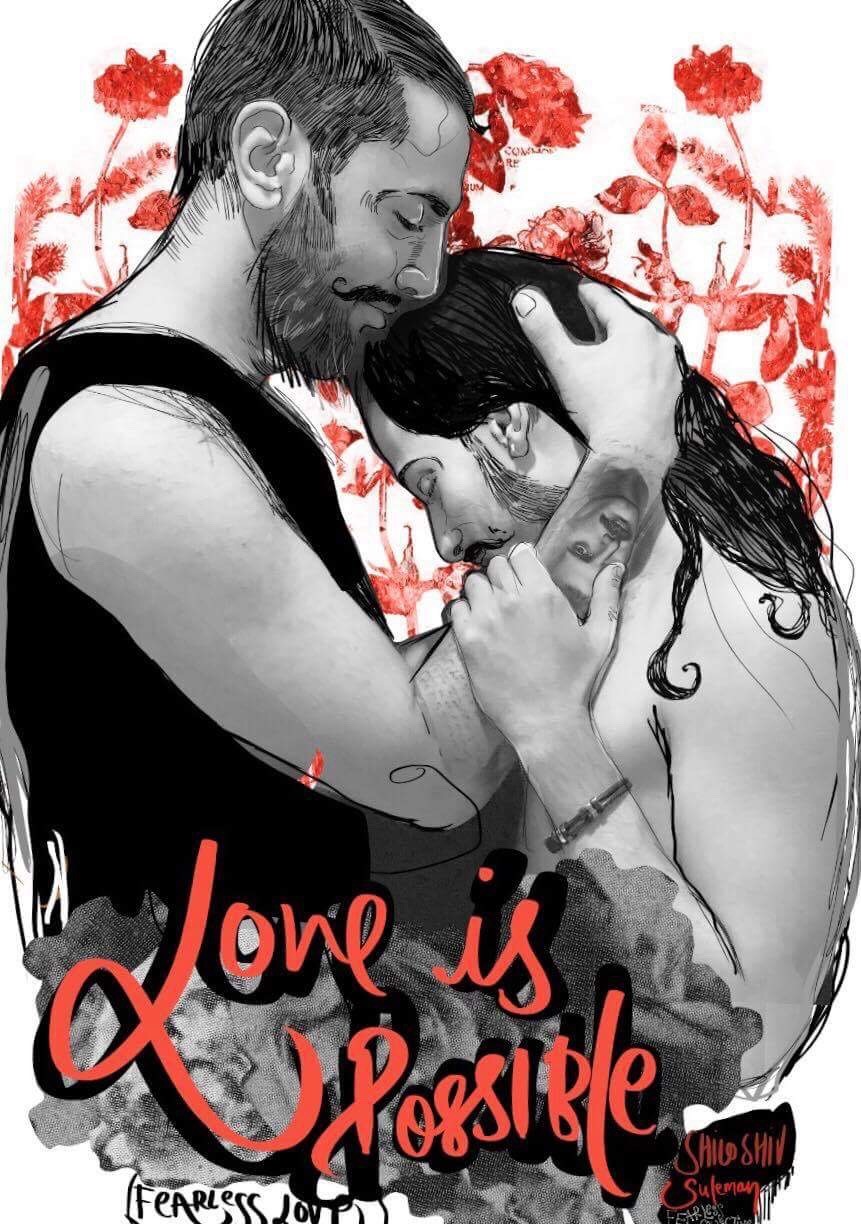

Some might say their relationship was not right. While Mamma’s family was quite progressive, no one had married out of caste. Pappa wasn’t even Hindu or Indian. But Mamma and Pappa were in love and brave. Luckily, Bapuji and Ba were also loving and brave. Despite some negative reactions from their community, they supported Mamma and soon treated Pappa as a son of their own. Pappa’s family was more difficult, especially his rather authoritarian and conservative Christian father. According to Mamma, it was only when I was born that he really accepted her and us.

I was born on the 6th September 1980 in Oslo, Norway. Raising me and my younger brother, Mamma tried to strike a balance between Norwegian culture and Indian culture. At the end of the Norwegian, Christian prayer we sang every night, she added some words of her own. “Amen, Ayu, Shanker Dada, Lirbai raksha karjo.” To me then Amen became one god among many. I now think of this act as one of queer creativeness.

Despite Mamma’s efforts to make a home for us, I was still a brown boy in a largely white, culturally Christian community. I often felt like an outsider. When I came out as gay, Mamma was initially upset because she thought my life would become even more difficult. I told her my life as a closeted gay was worse, that I wanted to be myself and express my love openly, and I wanted her support. A few years ago, Mamma joined me in the parade during Oslo Pride. She had a bunch of rainbow flags that she smilingly handed out to people, including more sceptical-looking spectators.

Oslo has remained my base, but I have spent much time in India, studying, working and travelling. I often feel like an outsider in India as well, but I have been welcomed into an Indian queer community. The struggle against colonial-era Section 377 has helped create this community. Magazines such as Gaylaxy and Pink Pages have published my poetry, fiction and non-fiction, and enabled me to read and connect with other queer Indians. Many of my best friends – including some ex-lovers – are queer Indians. This is my community.

“Congratulations, my beloved!” I woke up to these words on Thursday 6th September 2018. It was Daniel, my boyfriend. He continued to describe some of the elements of our love that he appreciates, that we can communicate honestly and with the warmth of loving awareness. “Congratulations also with the Indian Supreme Court verdict today,” he said, “I know that means so much to you.”

I logged onto Facebook. It was aflame with words and videos posted by queer Indian friends. I watched a news update. It woke up my brother who was sleeping in the next bed. “Happy birthday, Vikram!” I turned and smiled to him, already in tears of joy. “The verdict?” he asked. I nodded. We watched the news together, a tear or two in my brother’s eyes as well. I shared the video on Facebook along with these words:

“I am in tears of joy. My motherland has made a huge step in the direction of decolonisation and freedom for all.”

My brother asked if he could share it. “Of course,” I said. “The world really needs this now,” he said, “While there is increasing hate and discrimination in so many places against people who are seen as different, the Indian Supreme Court is taking a clear stand for love.”

We went downstairs for breakfast. We were strangers here in this hotel, yet I felt a sense of community. “Mr Vikram?” an older waiter – gay, I thought to myself – asked me. “Yes,” I said. He showed us to a table. Soon he returned with another waiter – Indian-origin, I thought to myself – singing happy birthday and carrying a cake. Mamma had arranged it. The older, gay waiter took a photo of us and the cake. “Grazie,” I said. “Prego, caro,” he said, and squeezed my shoulder and smiled and I appreciated the love. I sent the photo to Mamma on WhatsApp. She called and sang for me. I told her how grateful I was for this trip and for her love. I told her about the Indian Supreme Court verdict. “I am so glad, Vikram,” she said. “Jay Shree Ram.”

I continued celebrating via social media with queer friends in India. I read excerpts of the verdict and appreciated how the judges included poetry and looked outside of India for inspiration as well. This inclusiveness is perhaps the best of Indian culture, as well as of queer culture. I was in Verona, city of Romeo and Juliet, and the Indian Supreme Court quoted Shakespeare. “What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

Vikram’s latest book, Poetry Is Possible, is a selection of poems, coloured by his queerness, spirituality and dual heritage as Indian and Norwegian., can be bought here