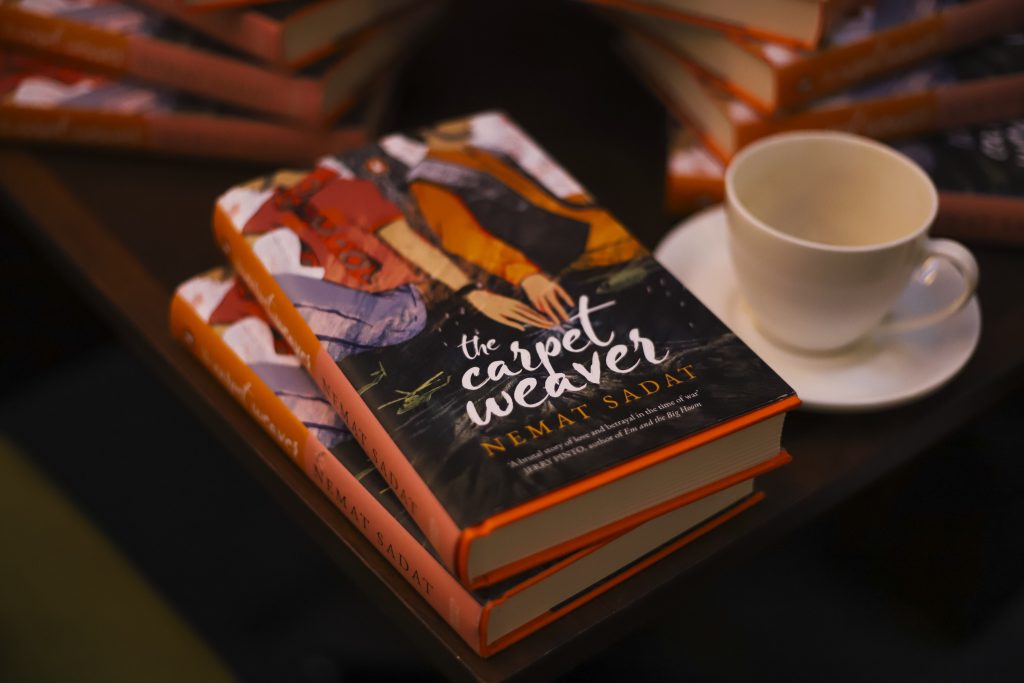

The Carpet Weaver grew out of my recurring pattern of unrequited love and the quest I embarked on to liberate myself from the mental shackles forged by homophobia and homesickness and being a repressed homosexual trapped between Afghan and American culture, between Islam and the West.

I was born in Kabul, Afghanistan in 1979, the year the Soviet invaded. The following year my family and I moved to Bonn after my father was appointed the Ambassador of Afghanistan to West Germany. In 1984, after the Parchami government in power in Afghanistan recalled my father, my mother refused to follow and raise me and my siblings in an Afghanistan afflicted by war and communism. Instead she would abduct me, my older brother and younger sister and take us to the US and I would begin my American experience of growing up in a low-income household led by a single parent among the Afghan Diaspora of Southern California.

From an early age, I experienced a profound sense of shame for being a homosexual male born into an entrenched culture of patriarchy that uniformly rejected tolerance for same-sex love. At the same time, I grappled with a sense of segregation as an ethnic minority growing up in exile in the United States. It terrified me that there was a part of me that neither Afghans nor Americans would be willing to accept. Then at age 20, my allegiance was questioned in the aftermath of the attacks of September 11, 2001 when my adopted land went to war with my homeland and my clashing identities were thrown into flux. The crisis I experienced prompted my intellectual awakening and I spent the next decade educating myself and trying to figure out how I was going to make my mark in the world.

During the year I lived in Afghanistan, I was persecuted for being irreverent, outspoken, and unapologetic about my unorthodox views about sex and sexuality.

In 2012, I returned to my homeland after living 32 years in exile, and embarked on my own journey to spread enlightenment ideals. Living in Kabul and working as a professor of political science at the American University of Afghanistan made me realize that I could no longer afford or stand to live my life with one foot in the closet and one foot out. Prior to that, I had a more complicated existence—not exactly working hard to deny or obscure the facts of my life to my family and the people in the community I grew up in, but never demanding that they openly confront and accept those facts either.

During the year I lived in Afghanistan, I was persecuted for being irreverent, outspoken, and unapologetic about my unorthodox views about sex and sexuality. Rumors circulated around Kabul that I was a practicing homosexual and lapsed Muslim. I realized I would be a tragic hero if I simply returned to my old situation in the known world of bitter exile and repressed homosexuality. Instead, I gradually campaigned for LGBTQ rights on social media and began to meet gay men at coffee shops and hotels across the capital. I waged a relentless fight against repression in Afghanistan that eventually gained traction and sparked a gay liberation movement and ignited a cultural war between Islamic sharia law and secular-progressive values.

After a second forced departure from Afghanistan, for being a national security threat and allegedly threatening the social order of Islam, I returned to the US realizing that I couldn’t be satisfied with the life I once lived and was considered undesirable by the dominant American culture that is inclined toward white racial superiority to the demise of others. And I was still the other.

On August 22, 2013 at around 2:30 a.m. from my bed in an apartment in New York City, I broadcast this message on Facebook:

“I’m so happy to have finished the process of ‘coming out’ to the entire world. Burden lifted forever. For the last few people in the planet who don’t know, let me tell you know: Yes, I’m proud to be gay, Afghan, American, and Muslim. So get over it! Now, I can life live without all the aunties & uncles harassing and pressuring me with questions like why I haven’t married a woman. If they do, I will simply shake my head, snap my finger, toss my hair and tell them I am marrying a distinguished gentleman and in Pashto we call it “khaawand” (owner, proprietor husband) and if you want to offer your son or nephew for my hand then tell him I want a platinum ring on my finger, a Central Park wedding ceremony and a Manhattan skyscraper rooftop reception afterwards. I have it all planned out. The bespoke lifestyle awaits. Oh yeah!”

I ended the internal turmoil raging in my head and received a tsunamy of hate—curses, condemnations, death threats, and even a fatwa, for publicizing my sexual preference and campaigning for LGBTQIA rights and gay marriage in Afghanistan and across the Muslim world. It was at this time that I had begun to see my coming out as something far more bigger than myself.

My story, at its core, is about the formation of a gay Afghan refugee from Muslim tradition who would come out and emerge as a transformational leader. After I came out I realized that The Carpet Weaver was not just about me or Kanishka. This novel became a voice and a vessel to all LGBTQIA throughout the East who are closeted because they fear for their life or imprisonment or other types of persecution. It gave my life purpose and terrified me that I was carrying the weight of the gay world on my back and that Kanishka was carrying the aspirations of all people who have been denied the freedom to live and love and reach their full potential.

Even in my darkest and loneliest days, living among the living dead in a homeless shelter in Brooklyn, I would find the strength to write The Carpet Weaver knowing that someday it will become a petition for changing the mindset of the world about the LGBTQIA community.

This novel became a voice and a vessel to all LGBTQIA throughout the East who are closeted because they fear for their life or imprisonment or other types of persecution.

When naysayers or obscurantists blocked my ambition to empower myself and emancipate others, it took an Indian to crack open the doors for me. Vikram Sura in giving me my first break in journalism by extending an internship to me at the United Nations Chronicle. Natasha Singh for hiring me as a production assistant at ABC News Nightline. My old boss Fareed Zakaria for pitching me to his colleagues to appear as a newsmaker and subject-matter expert on CNN after Omar Mateen—an Afghan, American, Muslim, and alleged repressed homosexual—committed the world’s largest massacre in recorded history against the LGBT community. Amal Chatterjee my tutor during my creative writing master’s degree at Oxford University for coaching me to finish the first draft of my manuscript and ensuring the timely completion of my creative writing master’s thesis. Kanishka Gupta, my literary agent and founder of Writer’s Side, for discovering the diamond in the rough that is The Carpet Weaver and Ambar Sahil Chatterjee for acquiring my novel and Penguin Random House India for launching it into the world.

And finally I want to mention the Indians who made The Carpet Weaver a breakout novel within the make-or-break period of the first 90 days. The Indian press who found literary merit in my work and published so many author profiles and book reviews that has made The Carpet Weaver the most written about debut fiction in India this year. The Indian blogger community who continue to champion the novel and spread the word about Kanishka Nurzada’s odyssey, the Indian LGBTQIA community for rallying around The Carpet Weaver as an activist tool in promoting universal human rights, and actress Sonali Bendre Behl for choosing The Carpet Weaver as book of the month in Sonali’s Book Club. The facts are clear. I would not be a novelist today without the presence of Indians in India and in the Diaspora believing in me and helping me in my journey. I am forever indebted to the Indian nation for making my dreams come true.

I may be Afghan by birth and blood and American by product and ingenuity. But I am Indian by soul and spirit. Today, before all of you I want to declare my coming out as Indian. I am that. I really am.

I don’t even want to imagine what my world would look like without my Indian influence. A world without India is a hellfire for Nemat Sadat. It’s a world that I refuse to live in. I would rather be dead. And this is coming from an ethical vegan who embraces life for all creatures.

I would not be a novelist today without the presence of Indians in India and in the Diaspora believing in me and helping me in my journey. I am forever indebted to the Indian nation for making my dreams come true.

That doesn’t mean everything Indians do or India does is right. No individual or nation is immune or short of its own set of hypocrisies and mythologies. What I’m saying is that the aspirational goals of Indian civilization, the dominant narrative uncorrupted throughout the ages, is one of harmony, pluralism, and peaceful coexistence with nature and humanity.

My idea of a true Indian is someone who actively works to break down the barriers and rejects hate by building bridges and spreading love around the world. I believe that am that person, or have become that person, and I and that is what I’m proud to come out and call myself an Indian.

This was the the subject of Nemat Sadat’s speech at the National Coming Out Day launch of The Carpet Weaver in Bangalore. A Hindi translation of it can be read here.

- Coming Out as Indian - November 23, 2019