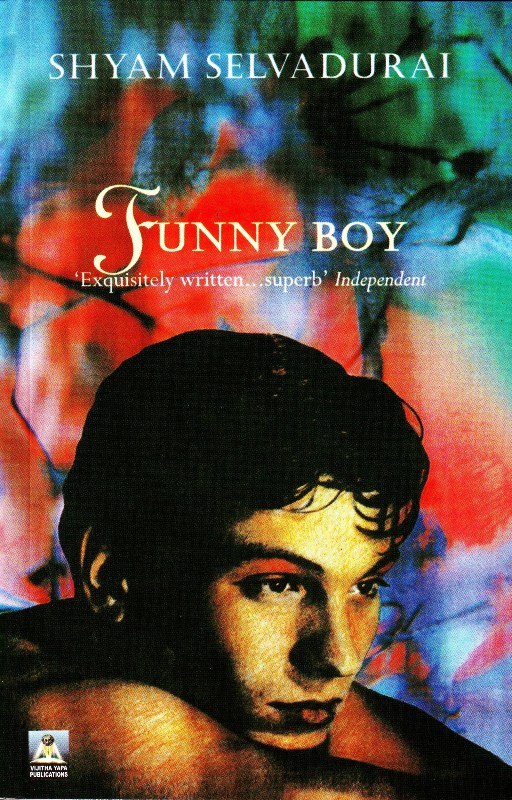

Winner of the Lambda Literary Award for gay male fiction and the Books in Canada First Novel Award, Syam Selvadurai’s debut Funny Boy is perhaps the most widely read and appreciated LGBT themed novel in the subcontinent. It was also one of the most talked about book till recently within the academic circle in Delhi ever since FYUP included it in the B.A. English syllabus though it had been scrapped off along with FYUP earlier this year.

I finally picked up this book from a friend’s bookshelf recently when I stayed overnight at his place. Honestly, the beginning of the novel; the episodes of doll-playing with the girls and Arjie wearing the sari in the bride-bride games in the first chapter gets a bit clichéd. Why does a queer male have to have necessarily played such games in childhood? And why does the writer have to create such a childhood for Arjie? Is that the only way to tell a queer tale? This not-so convincing beginning is surprisingly complemented and balanced by a much more powerful and nuanced chapter The Best School of All, the second last. The politics of queer relationship and representation get much more nuanced there; no over the top clichéd and stereotypes are employed in portraying Arjie and Shehan’s identities and their relationship. There is neither any emphasis on the physical agility or feebleness of the boys nor behavioural characteristics charted out for them (queer people are often carved on certain stereotypes even in literature). At the same time, these two chapters also reveal how queer, both as a subject/individual and a way of life, is subjected to discrimination and ridicule. The queer occupy luminal or no space at all in the society. Selvadurai’s book explores this luminal queer space through the two characters and their conjoined circumstances.

Set against the backdrop of the political turmoil in Sri Lanka leading up to the 1983 riots, this novel is about a young boy whose childhood is different from others. It is about his experience of homosexual love and relationship with a disturbed yet strong-headed and far too intelligent boy from his class. The novel tells you how far a boy like Arjie is going to go ahead and risk everything for what he considers love. But Arjie or Shehan are not the only ones who are forbidden from their loved ones, Radha (Arjie’s aunty) and Amma (Arjie’s mother) also find themselves forbidden from their loved ones and end in tragic separations. Shehan not only deals with the anxiety of his rather short-lived relationship with Arjie, he also has to bear the absence of his dearest ones. After his parents’ divorce, his mother left for abroad and throughout the novel he tries to come into terms with her absence. Having said all these, this is a novel about Sri Lanka at the core of it. It is largely about the ethnic tension and clashes between the Tamils and Sinhalese during the 1980’s. It also tries to capture, apart from the ethnic tension, the collective and individual confrontations of class, gender and sexuality in that society. The novel can be read as a serious discussion about space and place within which notions of freedom and identity are played out. It’s also about the politics of the luminal spaces, either real and physical spaces in the form of property, house, or a room etc which are more open to transformation at the will of the subjects (Shehan’s room in his house or the garage where Arjie and Shehan make out aren’t necessarily queer spaces till they invade and manipulate).

The novel is multilayered and dense and hence there can be different ways of reading it. One way is to read it as a book about forbidden love and relationships, about people’s secrets and their deepest yearnings that are always refuted from realisation by different forces. In the Freudian sense it is the repression of the human desire. Hence it can be simultaneously read as an exposition on the idea of freedom. To forbid is to disrobe somebody’s freedom. In the different stories freedom is essentially found to be denied. And one is completely aware of the consequences in which people can be driven to when such an essential aspect is denied to people. Apart from the denial of a relationship or pursuit one delights in, which is a very personal and individual narrative, the riot that is recorded at the end shows that the collective freedom of the Tamils is taken away reducing them to the status of refugee or statelessness and whatsoever. The book asks what happens when such basic freedom, right, property, etc are denied to people. Definitely there is a whole shift in the existential experience of the people. Alienation is one of them. Not just Radha or Arjie or Shehan go through feelings of alienation because of reasons particular to them other characters also go through their own sense of alienations in their own ways; individual or collective. The writer weaves these different themes and narratives together with ease and spontaneity to tell a story which is at once very “Sri-Lankan” but also equally personal and yet universal (alienation) at the same time. This is precisely the strength of the novel.

The strength of the novel is that it brings together different narratives of love and taboo, which is human’s most profoundly unfortunate truth together while the larger tensions surrounding these people are kept intact throughout. The novel also implies that it’s not just the queer identity and relationship which are tabooed; women (Radha) who question hetero-normative and patriarchal structures are equally tabooed. People who refute the collective ethnic ethos are also be deemed as outcasts in a society like this one. Love doesn’t triumph in their stories because to love indeed is to be tabooed. Such personal narratives are often obscured and engulfed by stronger and larger forces of collective narratives; of nationalism and ethnicity, of social values and traditions leaving almost no scope for individual choice and reason. The riot engulfs and obscures the fate of the Tamils at the end. Each of the story ends in grief. The writer makes no attempt to humanize the stories at all. They are told as they would have happened.

- In Conversation with Priyakanta Laishram, A Young Manipuri Filmmaker - March 6, 2017

- This Music Video Starring Monica Dogra and Anushka Manchanda is so Bold, It Might Just Get Banned in India! - December 2, 2016

- “Art is Varied and Inclusive, But Unfortunately Humanity Isn’t” – An Interview with Singer Sharif D Rangnekar - November 21, 2016